Who Ever heard of a Diesel Engine?

By Thomas E. Stimson, Jr

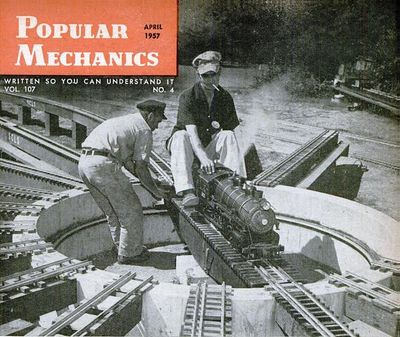

Popular Mechanics, April 1957

--Not the railroad fans, whose back-yard lines are burgeoning with snorting steam locomotives.

Big news at the Goleta Valley Railroad is that an automatic block-signal system is going to be installed along the entire line and that a tunnel is to be driven through a mountain. Seymour F. Johnson, president of the railroad, says the improvement program also includes installing a river under an existing trestle.

Instead of being a multi-million-dollar program, total costs will only amount to a mere hundred dollars or so.

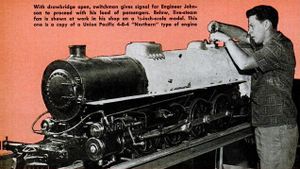

This railroad has only one locomotive, an oil burner of the Union Pacific 825 class, and when traffic is heavy the presidents of other nearby railroads bring over their own engines. That's why the automatic block signals are wanted. An engineer feels safer if he has a green board in front of him when several trains are operating on the half mile of track. Goleta Valley is proud of its safety record. It hasn't hurt a passenger from the time operations began.

And it isn't likely to. Located near Santa Barbara, Calif., the railroad is a 1-1/2 inch scale model of a full-sized system. Its "live steam" locomotive operates at scale speeds of up to 85 miles per hour but actually this amounds to only 10 miles per hour. The engine develops 10 horsepower and is calculated to be able to pull 14 tons on level track. It can haul 37 people up a two-percent grade.

Johnson started work on his engine in 1947 and finished it in 1951, thus by live-steam tradition the engine bears the number 4751. Building the engine was only the start, however. Next he needed a track on which to operate the live steamer and some cars for it to pull. Today he has 2500 feet of track consisting of Duralumin rails space 7-1/2 inches apart and attached by 30,000 tiny aluminum spikes to the 7500 small wooden ties in the ballasted road bed.

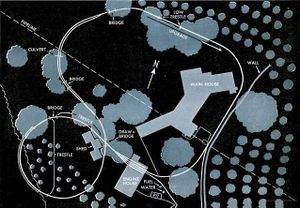

This track starts out by making a big loop, partly on a curved trestle and partly through a cut, returning under itself by means of a drawbridge, and continuing on across garden areas to make a big sweep around Johnson's residence.

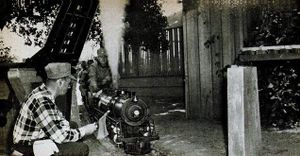

The engine shed consists of a garage built across the tracks, with an overhead door at each end. Typical railroad water-and-fuel tanks scaled down to size are located alongside the track for servicing the engine. The track system includes a long passing track, various short trestles and bridges, and the usual railroad warning signs, informational signs and signboards that announce the approach to towns. There is a "Y" track that permits turning the engine or a train around.

A spur track runs down Johnson's entrance driveway and this is handy on those afternoons when he holds open house. While johnson is hauling on trainload of visitors around the system, Dr. J. W. Newton and his 1-1/2 inch scale diesel switcher (powered by a storage battery at present) are making up a new train and loading passengers on the spur, ready for the next trip.

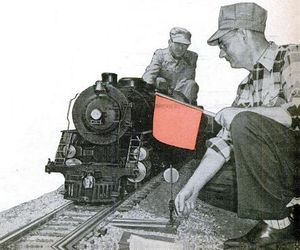

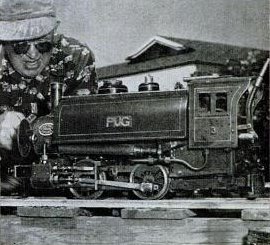

Walt Disney hauls passengers with his scale-model live steamer Lilly Belle over railroad on his estate

"Running a live steamer is fun," says Johnson, "but don't think for a minute that the engine is a toy. Far from it. The locomotive alone weighs 1250 pounds, the tender another 500 pounds. Drive wheels on the locomotive are 10 inches in diameter. Just like its prototype, the miniature engine has all the standard controls for the engineer to operate. These include throttle, reverse lever and air brake. There are gauges in the locomotive cab that show boiler pressure, air-brake pressure and the pressure in the reserve air tank. The reserve air supply is carried in a tank car behind the tender."

Rolling stock on the Goleta Valley Railroad includes half-a-dozen steel gondolas, a wooden gondola, a "beet" car and three flats. All have ball-bearing trucks; each is fully sprung; all have standard automatic couplers. Except for size they are true duplicates of actual railroad cars.

The Goleta Valley line is an outstanding example of a mechanical hobby that once had few enthusiasts but that is now growing rapidly in many parts of the world. Once it took special skills and know-how to build a small engine that would actually steam under its own power along a track; today almost anyone with mechanical ability and access to a few tools can build a live steamer.

The hobby is actually a kind of double-barreled pastime. First there's the satisfaction of building an intricate piece of machinery that works just like its prototype; then there's the thrill of operating the engine and listening to the "chuff chuff" of the exhaust and the roar of steam when the safety valve pops.

The smallest practical live steamers are built to 1/4 inch scale and operate on ordinary O-gauge track. Next is the 1/2 inch scale class, using a 2-1/2 inch track, then the 3/4 inch scale on 3-1/2 inch track, the 1-inch scale on 4-1/4 inch track, and finally the big 1-1/2 inch scale models. The 1-inch scale is the most popular. An engine built one inch to the foot is large enough for easy construction and for riding on the tender comfortably, yet small enough to transport in an average automobile.

Down around Los Angeles the 120 members of the Southern California Live Steamers have built nearly 100 different engines and have some 60 more under construction. The club maintains its own layout with two main tracks, each with three rails so that the various gauges can be accommodated. The system includes a turn-table from which radiate a number of steaming tracks that take the place of a roundhouse. On the steaming tracks the individual engines are fueled and watered and fired up before moving out onto the main lines. Sometimes it's hard to get a good fire going in a diminutive engine and often a vacuum cleaner is used to create a forced draft through the firebox. Coal is the favorite fuel, though fuel oil or butane gas may be used with special installations.

Liek other live-steamer clubs in other parts of the country, the Southern California Live Steamers consists of members from a dozen or so different trades and professions, all drawn together by their love for the little engines. Bob Furlong, the president, is a diesel engineer. He started out by building a 1/2-inch B&O steamer, now has completed a 1-inch Atlantic type. Member Walt Disney has his own Carolwood Pacific Railroad, a half mile long, at his home. On this he operates his 1-1/2 inch scale model Lilly Belle, a copy of the old Central Pacific's engine No. 173 that was built in the sacramento shops in 1972. David Rose, the composer, has a 1-inch-scale model; Ward Kimball, cartoonist who also maintains a full-sized old-time locomotive at home, has a 3/4 inch scale model live steamer.

Makes Own Drawings

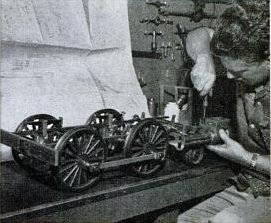

Few enthisiasts start from scratch these days the way Ray Gifford, a Lost Angeles toolmaker, built his engine. Gifford started out with nothing more than a few ancient shop prints of a 10-wheeler once built for the Denver & Rio Grande line. From these drawings Gofford made his own drawings scaled down to 1-1/2 inches to the foot, then designed and built his own patters, made his own castings and, bit by bit, made all the rest of the parts.

In the past, anyone who wanted to build a live steamer had to do it that way. Sometimes you could borrow the patterns from someone else who had built a small engine but usually you had to start in at the beginning. Often an engine took years of part-time work to complete.

It's a lot easier today. A number of concerns, notably Little Engines of Lomita, Calif., will supply you with individual parts or will make up a kit from which you can build an entire locomtoive. You can build as many parts as you like, buy the rest. You can buy the entire engine in the form of rough castings and do your own machine work. For this you need a lathe, drill press, grinder and miscellaneous hand tools. Or you can buy most of the parts already machined and put them together with nothing more than hand tools and a 1/4 inch power drill. A few engines such as the 1-1/2 inch model of the old C. P. Huntington can be purchased on a virtual bolt-together basis.

Little Engines stocks the parts for a score of different models ranging from a 4-6-4 Hudson in 1/4 inch scale to the big 1-1/2 inch scale 4-8-4 Northern and 4-6-2 Pacific types. Depending on size and on how much of the work you plan to do yourself, a live steamer will cost you anywhere from around $120 to as much as $800. Most enthusiasts buy a few parts, do the machine work that is called for in the drawings that are furnished with the parts, then order the parts that they need next. That way, they space out the costs all the time the engine is under construction.

Frames Cost $14

As examples, here are a few prices for parts for a 1-inch scale 4-6-2 Pacific-type engine that weighs 225 pounds when completed: Main frames, $14 per set with no machining required; drive wheels, $15 per set as rough castings, an additional $3.25 per wheel if completely machined for you. Steam-boiler parts ready for assembly by brazing the parts together are available as a package for 433. Cylinder heads cost $3 each; cylinder-head covers are priced at $5.

Counting all the castings, sheet-metal shapes and small parts including bolts and nuts, there are some 500 parts in an average live steamer. On an average, a year's sparetime work is needed to put one of them together.

In a few respects a miniature live steamer is not a precise scale model of a big engine. if a boiler were fully scaled down, for instance, its walls would be too thin for safety. So the boiler shell is always built thicker and stronger than scale. Too, the valve gear is usually oversize so that the engine can pull heavy loads without breaking down. And some of the boiler fittings and piping are a little oversize because otherwise they would not be practical.

These details can hardly be deteced, even by an old locomotive engineer who has spent years operating the same engine, full size. The more one of these veterans studies a scale model of a type that he used to drive, the more he marvels at the skill and patience of the enthusiast who put the little engine together.